January 31 Update: I tried to fix a line break a few minutes ago and voila! the entire page disappeared. I'll recreate the content but it'll take me some time. Bummer.

Jubilant (stem of jūbilāns, present participle of jūbilāre to shout,

whoop). What is jubilantly whooped herein is news of a recent event and

recent publications.

FIRSTLY, the first PoetryAssembly held outside of

Zuccotti Park was a great success. We were given a free slot at the Bowery Poetry Club, and we filled the club. A few poets used the People's Mic, but otherwise, stood and addressed the circle.

The rest of my news:

3 poems in Reconfigurations: A Journal for Poetics & Poetry / Literature & Culture.

2 poems in Truck: RESOLUTION/REVOLUTION, curated by Larissa Shmailo.

1 short story, "An Archive of Paranormal Inquiry Into Coping," previously published in The Writing Disorder, now anthologized in The Writing Disorder, Anthology, Volume 2, 2012.

1 essay and 2 poems published on Poets on the Great Recession.

Sunday, January 29, 2012

Friday, January 27, 2012

Mad Crazy Love. 3 Years Later, Jane Eyre. Charlotte Bronte. She Endured.

|

| Professor Heger, maybe 20 years after Charlotte worked for his family. |

I cannot separate Charlotte Bronte from the collective

female. Her poems are, perhaps, undistinguished. (Emily Bronte has

three poems on Poets.org but Charlotte has none.) But she (and Emily) towers over literature.

And that's why my first reaction to the news that Charlotte's love letters were being published today was dismay. Can't we allow the woman a little privacy? Many, female and male alike, have known torments and grief of illusion and unrequited love. Whole industries serve that impulse with how-to books, including the classic of my generation, Women Who Love Too Much, with its iterations for men and across all gender preferences.

But what next struck me about Charlotte's infatuation with her employer Professor Constantin Heger, an older man with a wife and children (this when she was a governess in Belgium), was the timeline.

So she's 28, and that's a Victorian 28, not a wise, once-divorced 28 of the new millennium. She falls in love, whatever love is.

And three years later, when she's 31, publishes Jane Eyre. This is not Medea killing her children because of Jason's infidelity. This is not Dido, self-immolating when Aeneas dumps her. (Both accomplished women, myths surely based on flesh and blood.) Charlotte's life, however, doesn't end. It just has a bump.

I'm posting this article from the Telegraph here

BECAUSE I can't separate Charlotte Bronte from the collective female

which she advanced and amplified.

Stupid crazy love, yes.

Three years later, Jane Eyre. One hundred years later? A television or movie re-envisioning of Jane Eyre practically every other year. A book which remains a favorite for readers and critics. A woman who endures.

Sunday, January 22, 2012

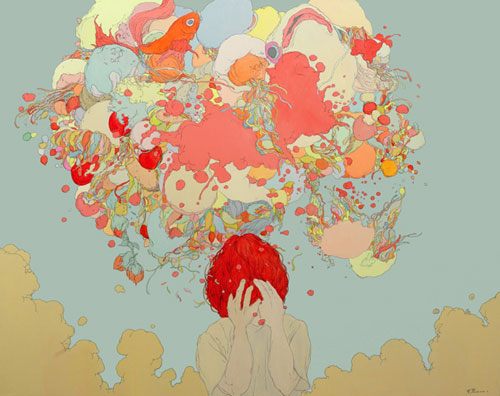

What will the indecipherable future dream? ... Borges (Still missing Etta & Johnny)

|

| Ric Nagualero* |

Every so often I'm proud of the human race. We don't have much capacity to identify stupidity, but sometimes we do know genius.

Tonight I'm going to post another selection from Poems of the Night, a gathering of work from several of Jorge Luis Borges' collections. I want, for myself, his easy passage into dream and back, his understanding of depth, process and transparency of the collective unconsciousness, of the momentous occasion of its existence, and a personal access through myth and dream (and good fortune). Borges gives me hope as an artist and as a believer (in many things).

Each sentence below is a meditation.

Someone Will Dream

What will the indecipherable future dream? A dream that Alonso Quijano can be Don Quixote without leaving his village and his books. A dream that the eve of Ulysses can be more prodigious than the poem that recounts his hardships. Dreaming human generations that will not recognize the name of Ulysses. Dreaming dreams more precise than today's wakefulness. A dream that we will be able to do miracles and that we won't do them, because it will be more real to imagine them. Dreaming worlds so intense that the voice of one bird could kill you. Dreaming that to forget and to remember can be voluntary actions, not aggressions or gifts of chance. A dream that we shall see with our whole body, as Milton wished from the shadow of those tender orbs, his eyes. Dreaming a world without machines and without that afflicted machine, the body. Life is not a dream, Novalis writes, but can become a dream.

Suzanne Jill Levine tr.

_____________

Borges, Waiting for the Night, Poems of the Night (Penguin).

*Painting by Ric Nagualero: www.nagualero.com / Facebook.com/nagualero

Friday, January 20, 2012

Great Souls Creating Their Own Proximity: Etta James & Johnny Otis. America's Great Black Musical Triumph. A Poem by Pessoa.

A great soul creates its own proximity. I don't need to have seen or touched Etta James or Johnny Otis to have been touched by them and in some way seen, my raging heart witnessed and deafened, especially by Etta. My life was as, hey, more, enriched by their presence on the planet as by any number of people I've shook hands with, taken classes with, received paychecks from.

As you know they were astonishing soul musicians. Neither had to make the choice to be other than messengers, though for Johnny Otis, a Greek American, there was a transition and it was a bit more conscious than Etta's. She was black. He wasn't, but Johnny Otis understood himself to be a musician in the tradition and community of America's great black musical triumph. He decided to move in that community very early in his career. Otis was a different kind of beautiful.

Miss James was all kinds of beautiful.

So to honor them I wanted to post a poem about joy and about humility, the true victory. The True Victory. Which is, at least as of 6:30 p.m., 1/20, to have lived and understood the meaning of all this, which is to say the humiliations and sufferings, the rapture of being alive. I don't presume to say they did or didn't understanding what I naively refer to as "the meaning." Like I do?

I bow to them.

Courtesy of Fernando Pessoa:

XVIII

If only I were the dust on the road

And the feet of the poor were tromping on me...

If only I were the flowing rivers

And there were washerwomen on my bank...

If only I were the poplars next to the river

And only had the sky above me and the water below me...

If only I were a miller’s donkey

And he beat me and valued me...

Better those than someone going through life

Looking back and feeling sorry about it...

____

Pessoa, 1914 (Portugal), from http://alberto-caeiro.blogspot.com/

Thursday, January 19, 2012

"In My Room" ... Brian Wilson & the Boys of Beach

So, okay. I knew very little about myself back then. Some little nub poked my psyche. Not that I thought about it. I was in junior high. I was in my room and my room was still a retreat much needed.

Sometime in the early seventies, my musician sister told me Wilson's composition compared with Bach's. I believed her but still can't say I had any place inside me, any room in which to consider that statement in depth. I experienced songs, felt them, didn't necessarily analyze.

While I didn't, then, disapprove of "In My Room," I sure didn't get the striped shirt-look of the The Beach Boys. It is good that they reformed and got sloppy.

Thank you, Sarah Sarai's parents,* for never ever objecting to rock, pop, r&b or soul, even though you were Bach, Beethoven, Brahms (and Rodgers and Hart)-happy.

By the way, I've wanted to read Wilson's autobiography, Wouldn't It Be Nice since it was published, but there were layers of glass between me and the book. The layers dissolved like sin in the grace of the Noon-day sun, a month ago. Yeah, it was a great read, and yeah, for me, a necessary read, if only to hear about art and rawness, transparency, filters.

Though not a great poem, it is a great song. Lyrics to "In My Room":

There's a world where I can go and tell my secrets to

In my room, in my room

In this world I lock out all my worries and my fears

In my room, in my room

Do my dreaming and my scheming

Lie awake and pray

Do my crying and my sighing

Laugh at yesterday

Now it's dark and I'm alone

But I won't be afraid

In my room, in my room

In my room, in my room

In my room, in my room

_______

Brian Wilson and Gary Usher

***back then I was Sarah Gancher...

Sunday, January 15, 2012

You Open to the World ("you" vs "I" in a poem)

I'm working on a new poem. It's a mystery how it came into life although the midwife is enough gifted and magically so, it's a mystery why I say it's a mystery.

Second poem in a row I've opened a collection of Borges' poems and found a word to start me. When you think of Borges, with his bottomless knowledge of myth and bottomless well of mythical creation, it may seem a poor reflection on duncehead simple-minded me that the word was, in fact, "myth." But there you have it. When a girl is starting a new poem, she ingests the sure witchery without looking back, the sure transformation from emotion to word with gratitude and unquestioning acceptance.

I began:

The poem moves on to the hereafter and the here and now. Writing some days later, some drafts later, I realized that what satisfied me most about the poem--it's obvious hint of self-revelation--worked against the poem opening to the universal and becoming more than confessional. So (with the second stanza added here) I changed pronouns:Myth is the man with the hook

cramped on the door handle of

my family's red Rambler. Seems

I'm about to leak the hue's variant,

a worser rose oxidized in

Mulholland's moist night air.

Myth is the man with his hook

cramped on the door handle of

your family's red Rambler.

Seems you're about to leak the hue's

variant, a worser rose oxidized in

Mulholland's moist night air.

As a reader I'm now more excited about the poem, where it's heading. I have a tingling sense of participation. Granted, I'm easy, a willing participant, happy to be suspended in disbelief, more so after the change because I'm a "you."Your death will be a mystery because

you don't drive on Mulholland at night.

This poem, currently "Poem for Mr. Sage," weaves death, the caring and uncaring universe, kindness, callousness, connection, family, a lover. I think it does, anyway. I believe the poem stands a better chance of being what I just promised it was, with the pronoun substitution. YOU, dear reader, are invited in through more stanzas, more transformation.

Wednesday, January 11, 2012

Pessoa, Bossa Nova, "I'm in no hurry." A Pessoa poem.

|

Beatriz Milhazes (Brazilian, 1960) |

But this thought, which, really (or as you might suspect), just occurred to me, does incline me to transmigrate my soul into a Portuguese-speaking body, and, while we are at it, in Brazil rather than Portugal. I'm always eager to escape European shadows though Pessoa's is a shadow providing sun.

Hey, ignore me and read this poem which I found on http://alberto-caeiro.blogspot.com/. A better blogger than myself would rethink her freewheeling associations and present interpretation. I am not the better blogger. Heart heart Pessoa. This poem is not titled.

I’m in no hurry. What for?

The sun and moon aren’t in a hurry: they’re right.

Hurrying is believing people can get past their legs,

Or that, jumping, they can land past their shadow.

No; I don’t know how to hurry.

If I stretch out my arm, I get exactly where my arm gets---

Not even a centimeter farther.

I only touch where I touch, not where I think.

I can only sit down where I am.

And that’s funny like all really true truths,

But what’s really funny is that we’re always thinking something else,

And we live truant from our reality.

And we’re always outside it because we’re here.

__________________

Fernando Pessoa / Alberto Caeiro (6/20/1919)

Monday, January 9, 2012

Legislators of the World (There Should be a Club in High School)

|

| from The African Tarot |

Yesterday I was with a group of poets toward the end of the day, toward the end of the weekend. None of us could remember the exact quote or the correct poet.

I shamefacedly, humbly admit I came up with Keats, Auden and Eliot. Why not Shakespeare? Why not the Bible, with whom Ben Franklin has been confused, quote wise.

It was easy enough to Google and even more fun to Google an image. My Tarot deck is the Haindl, but that's a tricky deck to find online. It's so beautiful and very mysterious. I am very happy, however, to have discovered The African Tarot. Sleek and otherworldly.

Of course Shelley wasn't thinking about Tarot decks when he wrote In Defense of Poetry, though I wouldn't be surprised if he or any of the Romantics studied Tarot. Many poets have. I keep getting sidelined.

Here is the quotation in full. As you know, a hierophant is a priestess or priest, an interpreter of sacred mysteries or arcane knowledge.

Poets are the hierophants of an unapprehended inspiration; the mirrors of the gigantic shadows which futurity casts upon the present; the words which express what they understand not; the trumpets which sing to battle, and feel not what they inspire; the influence which is moved not, but moves. Poets are the unacknowledged legislators of the world. Percy Bysshe Shelley

Sunday, January 8, 2012

Fiction: Dream Bed. A short story from 1988.

Dream Bed

by Sarah Sarai

{Reprinted from The Written Arts. King County Arts Commission, Seattle, WA}

by Sarah Sarai

{Reprinted from The Written Arts. King County Arts Commission, Seattle, WA}

My nineteenth summer, before my Sophomore year, I went to San Francisco to stay with Fredric, an old friend of my newly divorced parents. I was given a bedroom facing the afternoon sun, the setting sun. Its bed was double-sized and more than soft. The sinking pliancy was empyrean. So cushioning and tranquilizing was that bed, I slept from ten at night to ten by day, or nine to nine, or eleven to eleven, making my waking life a half-life or my life of dreams and imagination the same. Altogether, the effect was that of living an evenly divided sphere of waking and sleeping so balanced and contiguous, all summer was a rhythmic lap of waves on a mirror-smooth sheathing.

Each morning Fredric ground coffee and whisked eggs. He’d scout European bakeries for heavy, dark bread on which we’d smear avocados, then salt and pepper them for our lunch. Our dinners were seafood sweetly simmered in wines and sherries, roasts lovingly coddled, basted as often as sleeping infants are checked by tender mothers. I was as treasured as rare beef; a delight under any circumstances I’m sure, and a necessary slab of humanity in these circumstances. Fredric’s lover had left a few months before my stay. Friends still visited to join in lamentation, as if for the dead.

“Nola, Lon was tops for Fredric, that’s for sure,” I’d hear.

“He was such a beautiful man.”

“So kind.”

“And handsome.”

“So smart.”

“I thought Fredric should have kicked Lon out long ago. Lon’s cold.”

“He was offered a job with a public relations firm. He wanted it more than he wanted me. What could I say?” Fredric explained when the guests had gone and we were still seated, fiddling with the pie’s crust. “Well, of course I tried and said everything, but none of it took. The Sunday before he left we saw a play matinee, then a movie, then a cabaret that evening. He indulged me. Who else will do that?”

I fell asleep sad that night.

I woke one morning to find him moored on my bed. “Let’s go.” He tapped my arm. We drove to Ocean Beach where he and Lon had talked. He pointed to the very wave that pounded Lon’s moving announcement.

“Each time he spoke my stomach opened like an anemone and was crushed by his words.”

We sat, cold, on the sand.

“When I drove Lon to airport,” Fredric said, “I didn’t walk in with him. We stayed in the car until he almost missed his flight. Both of us were crying. Both of our hearts were broken and we knew it.

“Death may hit hard, Nola, but there’s nothing like lost love for a full emotional sweep. Maybe it would help if I had an office to go to. I should buy another restaurant instead of living off my past laurels.” My parents had met him while dining at his spare, moderate and fabulous establishment.

I heard Fredric moving around in the kitchen that same night.

“I’m sorry to wake you.” He stroked my hair.

“It’s okay.”

He threw a dish towel on the counter. “My nightmare ended and I had to get myself out of bed.”

I needed an explanation.

“I was driving back from the desert, a resort in a desert, and I realized I’d left something behind and looked, someone else was driving, and I saw the Saguaro cactus twisting like ocean flora, then grow huge, then fade. Lon became a Saguaro, twisting on the horizon. I shouted, but he wouldn’t hear. I believed he wouldn’t hear, refused to hear.”

It was six in the morning; we stayed up. I ground coffee. Fredric made omelets and passed them under the broiler. The cheese-graced eggs puffed.

Another day I was reading in bed and heard him yell.

“His heart!”

“What?”

“When we were at the beach, Lon and I, we stuck close and quiet. Did I tell you this? That’s why we’d gone there, to work us out, peaceably. I’ve been remembering this, Nola. We didn’t talk after a while. I was trying to exude hope. I could feel Lon’s heart. It wouldn’t move. Mine kept pounding like the waves. I realized it always would, no matter what.”

“That you’d keep living.”

“Of course I’ll live. But I decided I’d never use any excuse, any excuse, to lose heart.” He lifted a glass I'd set on the bedstand. “That I wouldn’t be a downer, Nola. Like Lon. When I’m honest about him, I can admit he was a downer, cold, not willing to try.” The glass rattled with melted ice.

I trekked to and from the kitchen. “Drink,” I told him.

He put both hands around the glass I held out. “I was the one doing the thinking. I was the one hoping.”

“I understand hope,” I said, “but I understand wanting better.” I wanted the arts of history and prophecy abolished. The surprise divorce of my parents was an ambush of my innocent serenity. My world had been overturned and I not unreasonably saw their unhappiness as a threat to my future happiness; an indication of my future inabilities.

I never slept fitfully in Frederic’s house but I slept thickly one night and awoke fraught and coincidental to the phone’s ringing I sprang into the kitchen and yanked the receiver. My father was on the line. He talked and talked and I kept my ear dutifully glued. My friend was by my side by the time my father had finished.

“He drives me crazy!” It was my turn. “ He called to see if I’d talked to my mother recently because even though they’re miles apart, in all ways apart, he’s still attached. Of course he is. But he has to let meknow. ‘Your mother’s a good-looking woman,’ he says and I hear the clink of ice in the glass and more than o.j. is being poured.” I click my glass of spring water against his.

“‘You don’t understand any of this,’ my pop says, ‘you kids don’t understand. So have you been in touch with your mother? Your mother and I spent many years together. What do you know? What does your mother know, anyway? That temper of hers. Your mother should take care of herself. Your mother has some deep troubles. Maybe a psychologist would help. Have you considered that? Have you asked her?’ Finally, we said our good-byes. I was crying but I didn’t let him know.”

Fredric poured me coffee then raced out and returned with fresh raspberries from the little market on the corner and served crisp waffles under berries.

I walked and rode the bus that day, all over the city. Twice, cast-adrift men followed me and it was part my doing. By looking into faces, by trying to read character and nature, I connected with the vulnerable fringe. I had to divest myself of my enamorees, once by hopping on a bus, once by asking directions from a cop. When I returned home, I asked:

“How could you two break up after crying together about breaking up?”

“It was bad,” he conceded, “and it doesn’t make sense. I guess the heart isn’t connected to the brain; and I believe the body does have a deep wisdom. Maybe it’s too deep.”

I slept soundly that night and dozed the next day and slept even more deeply the following night and said to Fredric in the kitchen the next morning:

“It’s doomed. My future is doomed. My love future. All the information I’ve been given is deceptive.”

“Because your parents divorced?”

I stared. “All of it. Because everything they passed on that could lead me to believe I could live and love and do it all successfully, has been changed by the divorce.”

“Now, Nola . . .”

“No, listen,” I interrupted. “Something went wrong way back. Have I told you my aunt’s story? My mom told me. This was years ago when they were still living at home. Aunt Sheila fell totally in love. And he was totally in love with her. A nice guy, too, my mother said. They became engaged and he asked her if she’d work the first couple of years of the marriage so they could get ahead. Sheila refused and the engagement busted. She turned down her true love and then she cried for a year. Can you imagine that? She cried a whole year. My mother watched and vowed she’d never get hurt like that. Maybe she adored my father when she married him, but he wasn’t the man for my poor mother to love. So what chance do I have?”

“Thatisan awful story.” He turned the radio on and off. “They could make an opera about Sheila. I can see that kind of resolve in your mother. But didn’t you write last spring you were seeing someone?”

“Yes, and it was crappy. Thank God it didn’t last. Three months of begging for love.”

“You’re not the first.”

“Well, any begging is too much. I’d be at his place and it would be logical for me to spend the night and he’d say no and I’d have to ask a couple of times for him to relent. Who knows who’s right. It felt like begging and as I did it I swore I’d never do it in another romance. Do you believe romance and marriage is all no-fault?”

“Not always.” Fredric sounded balanced.

“He wanted everything his way. I stayed with him the last few days before finals were over and vacation began. I had one dream.” I described the dream:

“There was a light-skinned black woman. She had purple blemishes on her body, below the collarbone and across her cheeks. I thought they were splotches and began trying to be overtly sympathetic. Then I saw her boyfriend. He had the same markings. I inspected him. The blemishes were swirls in the marble. Both man and woman were statues. I touched them. The man was perfect. She crumbled.”

We busied ourselves. We beat eggs. We baked three layers of genoise; light, rich, spongy cake. The confectioners of heaven get orders for this sybaritic delight. Angels eat their namesake cake as an everyday dalliance and genoise for on-high holy days. We saturated it with rum, spread the layers with mocha cream and dropped slivered almonds on top. We both had unruly dreams that night. I dreamt hot butter was oozing from a chocolate bar and a chorus of shrill women were sighing in the background. Fredric dreamt the clouds were hurling black eggs, far too large to be coffee beans, on the city. He remembered regretting they weren’t coffee beans.

Several days later I was again resting and again I heard the phone ring. I’d just crawled into bed. The time was only 7:30 p.m. but an increasing despondency had prompted me, maybe dulled me, to choose an earlier shift in my bed-bound summer. I hadn’t yet patted the final pat on my pillows and therefore rolled without resentment onto the floor to answer the phone. My bed wasn’t going anywhere without me.

Lon was on the line. He asked for Fredric, who by this time was at my side, wrapped in a towel.

“I knew it,” he declared as he took the receiver from my hand. “I knew it would be you. I’ve been thinking of you in the bath. I was in the bath.” Fredric shooed me away, then grabbed me before I was farther than arms’ distance and pulled me to his moist towel and held me throughout the conversation. I was able to hear it all. Lon had overshot his mark in settling into luxury living and was in debt. The firm he worked for had provided moving expenses, and a big salary, but he’d been banking on a commission, too, and had spent with that in mind; apparently done betting and didn’t want to blemish his reputation in a new town. He asked to borrow money. Fredric was ecstatic.

“And I’ll send some right now, tonight, by Western Union.” He hung up the phone and turned to me. “Excuse me, my dear.” He ripped off the towel and shouted, “Hope!” He dressed and raced out with cash he kept under his mattress and I returned to my bed of dreams where I saw a moon rise and a lizard try to leap over it without success, then claw at its center.

I described this lizard the next morning. Fredric was delighted with the lizard—with everything. He was glad Lon had called. He hoped, with calculation, Lon would find his new life unfeasible, and return.

“And you’d take him back?” I asked.

“You think I shouldn’t?”

“Beats me what should happen. I just want to know.”

“Well, I would,” he said. “I refuse to give up. You haven’t met him. You’d like him.”

“How will I meet him? I’m leaving soon,” I moaned. “Where’d the summer go?”

“Nola, there’s so much we haven’t done.” He leaned on me, as friends do. “There’s so much we haven’t cooked. We must atone.”

“Let’s make pancakes.”

“Why not!” He set me to grating orange while placing pecans on a cookie tray for roasting. “Roasted pecan and orange pancakes. Nola, don’t bother with your degree. Stay here and eat your way into old age.”

The day before I left, there was a post card in the mail from Lon, from the Bahamas. He was on vacation and he wasn’t alone. Frederic didn’t say much, except he’d always been prepared for the worst. He went out and I wandered the apartment all day. He still hadn’t returned at midnight and I pulled back all the drapes so the moonlight aided by city light could enter. The rooms felt sallow and ill as I roamed the wooden floors for hours. Each thing in the apartment stood remote and objective in the night glow. Each thing looked distant and self-sufficient. Each thing was impersonal and I began to feel very lonely. I went to my room and stood at the window. The moon was full, almost bursting its sphere. I pushed my dream bed to the window so I could sink in and keep watch. I stared so long my gaze numbed. I slept. In my sleep I saw it happen. I looked to the night sky whose velvet was corroded by city light and with horrified eyes I saw the moon break. In a wrenching snap, the translucent twins cruelly outlined against the night sky, two things, two half-symbols, fell. I awoke shaking.

My mind flicked on and I began to bawl, unrelentingly, unremittingly, loudly and unceasingly. The giant tears poured onto the pillow and my sobs, at first muted by discretion, soon filled the air.

“Nola?” Fredric was in the room.

I kept crying.

“Don’t stop.” He held me.

I cried until I was drained and then I stopped.

“It’s almost four p.m. Why don’t we have high tea.”

“Do you have cookies?”

“Cookies!”he shouted. “High tea isn’t for cookies. We need cakes and pears. We need the tea of old Russia. Come and help.”

And so while Fredric zipped to the bakery and little market, I was set up at the kitchen table, polishing a samovar, making it bright. I lit the charcoals to brew the tea that could sustain all the Russias through a nineteenth-century winter. At the end of a warm and good summer, Fredric and I sipped mighty tea and nibbled rum cakes, pears and grapes.

We did this together.

________

________

Sarah Gancher Sarai. Reprinted with permission. The Written Arts.

King County Arts Commission, Seattle, WA. 1988.

Saturday, January 7, 2012

Dear 1 Percenters. Have I Too Glibly Addressed You?

|

| America's uncle. |

In my brief and poetically illustrated essay I address my audience directly, assume that “You” live a life similar to mine, that “You” have as negligible a bank balance as I do. You might. You might not.

What do I know? There are poets who make good bread, and more power to them. Ed Hirsch, who in addition to being poet and professor, heads the Guggenheim Foundation—seems like a good job. He deserves all and any monies, if only for How to Read a Poem and Fall in Love with Poetry. What a rare tribute to poetry and its readers that book is; it assures and creates more readers of poems.

I figure Rita Dove is doing okay, but then she teaches, has racked up some decent prizes and grants, and just edited the Penguin Anthology of Twentieth-Century American Poetry.

Cornelius Eady travels the world promoting poetry, encouraging poets of color—all colors and shapes and styles—to write. I've seen his and his wife's New York apartment—it's terrific but modest. Still he may have a little up his sleeve financially, being a teacher, and all. But Cornelius is not in the 1 percent, nor is Dove, and probably not even Hirsch.

Which leaves a silent member of the silent minority of 1 percenters to chance upon my work. Are you there, Ma'am or Sir? I'm interested in knowing. Let's meet at a bar, talk. If you like poetry or fiction, I like you. Okay?

***Poets on the Great Recession is a series of essays and poems curated by Eileen R. Tabios.

Thursday, January 5, 2012

The Dry Spell Is Over

|

| Art by Fan Zhou |

I'm not sure I know what that means, but shivers are sailing up and down my spine, matey. The main news here is good. Yesterday I didn't think I could write. This morning I got up and wrote. By "got up" I mean made two cups of coffee. By wrote, I mean remembered I title I decided on just as I was falling asleep.

Sometimes you get lucky and don't forget what you were thinking of the night before. I got lucky. Perhaps because title of my newest poem, "Rolling on the Floor Killing Elves," is not subtle. Perhaps because it is, in some form, archived in a series of comments, a conversation I had on FB with another poet. Whose name I withhold merely to protect her.

Who besides Sarah Sarai wants to be associated with "Rolling on the Floor Killing Elves." It may be dangerous to explore so much about spanking new work, but, well, I'll find out, soon enough. The thing is, the poem starts silly and self-evolves into a vehicle for dreams remembered and not, and a family member who never, until last night, visited one of my dreams.

I love creativity and the process. I love seeing words spill out of me in combinations I never before knew.

One more possible reason for the end of the siege. Last night I submitted two poems to a journal for which I tailored the poems. The poems weren't requested. There is no guaranty they will be accepted and a great margin of possibility they will be rejected. I wrote them after being told by an editor who had accepted one of my poems, once, my new work wasn't quite what this editor's readers were looking for. So I had, against all belief in the possibility of doing so, tailored my work. Then discovered the journal was closed to submissions.

But, lo! these many months later, submissions were opened, I tried. When one door opens, so do many many more. Keep your doors open, universe. Sarah Sarai is moving on in.

Tuesday, January 3, 2012

Horny for Creativity. The Tendency to Create.

"The fault, dear Brutus, is not in our stars, / But in ourselves, that we are underlings." Okay. So there is no word, mood, conviction, delineation of the condition by Shakespeare I dispute, but each piercing of our veil is state-dependent, maybe plot-, story- or historical-fact ("fact") dependent. I am no Caesar; whatever tragedies allotted me have been lived. I'm sure of that, and my surety is interesting.

I can't say another plane won't fly into a building, that my neighborhood won't become a shrine, again, to the lost; that the unpleasant, the shouldn't have happened happenings or memories from the past won't spring to action like Civil War reenactors. I can say my response and assessment instincts are changed. All that damn positive thinking has its impact.

Trying to break what feels like a creative dry spell I found this quotation: I can always be distracted by love, but eventually I get horny for my creativity. [Gilda Radner]

Amen, sister. Point is, well, a sigh. The impulse to explore this further has, as they say, fled. Seeding the fallow is what I'm doing, is the connecting thread and threat to this posting, my working out impulses and letting them work me creatively, however, whenever, but, preferably, soon.

Hey, does underling mean what we take it to mean, not that we (I) are beneath the fatey stars, but that we are under some a boss, the law, some (any) power. Whatever. We're not in control. Lack of control forces our hand, makes us trust. Calls us to a belief in the tendency to create.

I can't say another plane won't fly into a building, that my neighborhood won't become a shrine, again, to the lost; that the unpleasant, the shouldn't have happened happenings or memories from the past won't spring to action like Civil War reenactors. I can say my response and assessment instincts are changed. All that damn positive thinking has its impact.

Trying to break what feels like a creative dry spell I found this quotation: I can always be distracted by love, but eventually I get horny for my creativity. [Gilda Radner]

Amen, sister. Point is, well, a sigh. The impulse to explore this further has, as they say, fled. Seeding the fallow is what I'm doing, is the connecting thread and threat to this posting, my working out impulses and letting them work me creatively, however, whenever, but, preferably, soon.

Hey, does underling mean what we take it to mean, not that we (I) are beneath the fatey stars, but that we are under some a boss, the law, some (any) power. Whatever. We're not in control. Lack of control forces our hand, makes us trust. Calls us to a belief in the tendency to create.

History of the Night. Borges. I change "men" to "women"

Truth

is, I'm in a fallow period. Fallow, like a field in the Bible

awaiting a parable to make me spring me to life. I'm counting on Borges,

fate, luck, the odds, to change my tide, or to release me from laziness.

One

jumpstart is my appropriation and probably misappropriation of this poem. I read it four or five times today, and in each reading made an agreement with Borges that "men" was inclusive, a trope of language, of its time. And then as I copied it out, I was not happy.

I thought, no, Sarah, look for a poem by a woman. And I might have, except for the fact that this is a beautiful, haunting, terrifying, specific delineation. So I just changed the word "men" to the word "women" both times it's used. Borges is larger than that. Equally true is that none of us are larger. Most true: "History of the Night" is remarkable and you must read it. The night, the dark, fear, blindness, ancient braveries, masteries, the heavens in their velvet revolving.

By the way. Luis

de León was a Sixteenth Century Spanish priest. He was a guest of the Inquisition not once but twice, translator (Song of Songs), academic and poet.

History

of the Night

Down

through the generations

women

built the night.

In

the beginning it was blindness and sleep

and

thorns that tear the naked foot

and

fear of wolves.

We

shall never know who forged the word

for

the interval of shadow

which

divides the two twilights;

we

shall never know in what century it stood as a cipher

for

the space between the stars.

Other

women engendered the myth.

They

made it the mother of the tranquil Fates

who

weave destiny,

and

sacrificed black sheep to it

and

the cock which presages its end.

The

Chaldeans gave it twelve houses;

infinite

worlds, the Gateway.

Latin

hexameters gave it form

and

the terror of Pascal.

Luis

de León

saw it in the fatherland

of his

shuddering soul.

Now we

feel it to be inexhaustible

like

an ancient wine

and no

one can contemplate it without vertigo

and

time has charged it with eternity.

And to

think it would not exist

but

for those tenuous instruments, the eyes.

Jorge

Luis Borges, tr. Charles Tomlinson. Waiting for the Night, 1978-1985, in Poems of the Night, Penguin, 2010.

Sunday, January 1, 2012

Borges, my last of '11, my first of '12. "Someone," a poem

It seems the right thing, to remember the last poem I read in 2011, and to make it my first in 2012. It's from one of my bedside collections the past few months, Poems of the Night, a selection from three of Borges' books.

"Someone" ("Alguien" in Spanish) is from A Gift of Blindness, 1958-1977.

Like someone, I live with "reasons more terrible than a tiger." Please note and admire how Jorge Luis Borges defines our crouched fears as impossibly muscular.

This morning I jimmied a flyer for an Occupy Language event that will be held on January 26, 5-7:30, at the Bowery Poetry Club, and in hunting for a quote looked no further than James Baldwin. Every legend, moreover, contains its residium of truth, and the root function of language is to control the universe by describing it.

"...to control..." the universe seems too colonial, but "describing it," is just the ticket, a ticket I buy. Borges describes.

Someone

"Someone" ("Alguien" in Spanish) is from A Gift of Blindness, 1958-1977.

Like someone, I live with "reasons more terrible than a tiger." Please note and admire how Jorge Luis Borges defines our crouched fears as impossibly muscular.

This morning I jimmied a flyer for an Occupy Language event that will be held on January 26, 5-7:30, at the Bowery Poetry Club, and in hunting for a quote looked no further than James Baldwin. Every legend, moreover, contains its residium of truth, and the root function of language is to control the universe by describing it.

"...to control..." the universe seems too colonial, but "describing it," is just the ticket, a ticket I buy. Borges describes.

Someone

A

man worn down by time,

a

man who does not even expect death

(the

proofs of death are statistics

and

everyone runs the risk

of

being the first immortal),

a

man who has learned to express thanks

for

the days' modest alms:

sleep,

routine, the taste of water,

an

unsuspected etymology,

a

Latin or Saxon verse,

the

memory of a woman who left him

thirty

years ago now

whom

he can call to mind without bitterness,

a

man who is aware that the present

is

both future and oblivion,

a

man who has betrayed

and

has been betrayed,

may

feel suddenly, when crossing the street,

a

mysterious happiness

not

coming from the side of hope

but

from an ancient innocence,

from

his own roots or from some diffused god.

He

knows better than to look at it closely,

for

there are reasons more terrible than tigers

which

will prove to him

that

wretchedness is his duty,

but

he accepts humbly

this

felicity, this glimmer.

____________

Jorge Luis Borges, A Gift of Blindness, 1958-1977, in Poems of the Night, Penguin, 2010. (Many translators are listed.)

____________

Jorge Luis Borges, A Gift of Blindness, 1958-1977, in Poems of the Night, Penguin, 2010. (Many translators are listed.)

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)